What Might Copyrightable GenAI Content Look Like?

It’s a puzzle with no clear solution.

Yesterday, Epic Games boss Tim Sweeney made headlines when he stated: "We shouldn't assume all generative AI is terrible or infringing”. The comment was made in response to a story about a game creator who had 3.5 years of their work negated due to the rival gaming publisher Steam’s rejection of their game due to the developer using Generative AI in its development.

Earlier in the year, Valve, Steam’s parent company, forbade anyone from putting games on its platform if they had used Generative AI in any way — citing fears around copyright: “Stated plainly, our review process is a reflection of current copyright law and policies, not an added layer of our opinion. As these laws and policies evolve over time, so will our process.”

It is a fear that is not unfounded. Ever since the GenAI genie rocketed out of the bottle in November last year, copyright and Intellectual Property (IP) quickly took front and centre in the conversation.

A litany of lawsuits

Just last week, OpenAI responded to a pair of nearly identical class-action lawsuits from book authors alleged that ChatGPT was illegally trained on pirated copies of their books. Other Generative AI companies, like Stability AI, which distributes the image generator Stable Diffusion, have also been hit with copyright lawsuits — Getty Images is suing the company for allegedly training an AI model on more than 12 million Getty Images photos without authorisation.

Elsewhere, this week, a U.S. court ruled that a piece of art created by an AI that required no human input at all could not be copyrighted. This may seem fair to some — automated creative doesn’t sound particularly enticing — but how about when a person uses Generative AI tools to create work? Can that be copyrighted? As it stands, no. Last April a judge ruled against an artist who had used Midjourney to produce a comic.

How long can this last? Millions around the globe are already using these tools to create, and the sheer volume of outputs means that something is going to have to give.

It seems The United States Copyright Office somewhat agrees. The Congressional agency is now undertaking a study of the copyright law and policy issues raised by artificial intelligence (“AI”) systems, seeking comment on these issues including those involved in the use of copyrighted works to train AI models, the appropriate levels of transparency and disclosure with respect to the use of copyrighted works, and the legal status of AI-generated outputs (readers have until 18th October to send your thoughts).

As OpenAI said in their recent response, those "misconceive the scope of copyright, failing to take into account the limitations and exceptions (including fair use) that properly leave room for innovations like the large language models now at the forefront of artificial intelligence.”

Life is not fair use

Fair use is a good defence. Fair use relies on evaluating four key factors to determine if a work is sufficiently transformative or just a copy. These include the new work's purpose and nature, how much it borrows from the original, and the effect on the market for the original work. It is this last factor that is proving critical when looking at Generative AI.

Many artists, writers, journalists and other creatives argue that AI-generated content negatively impacts them. It potentially reduces the commercial value and market opportunities for their original works. Generative AI aims to create new works derived from copyrighted source material and so it directly relates to this fourth fair use factor of market harm. It is likely then that the market impact will be central to legally assessing if AI outputs qualify as fair use or non-permitted copying in the years ahead.

This argument is the tip of the intellectual property iceberg: copyright is but one specific type of IP and protects works of authorship but not the underlying ideas. Other forms of IP can be much less tangible — encompassing more assets like patents, trademarks, trade secrets and industrial designs.

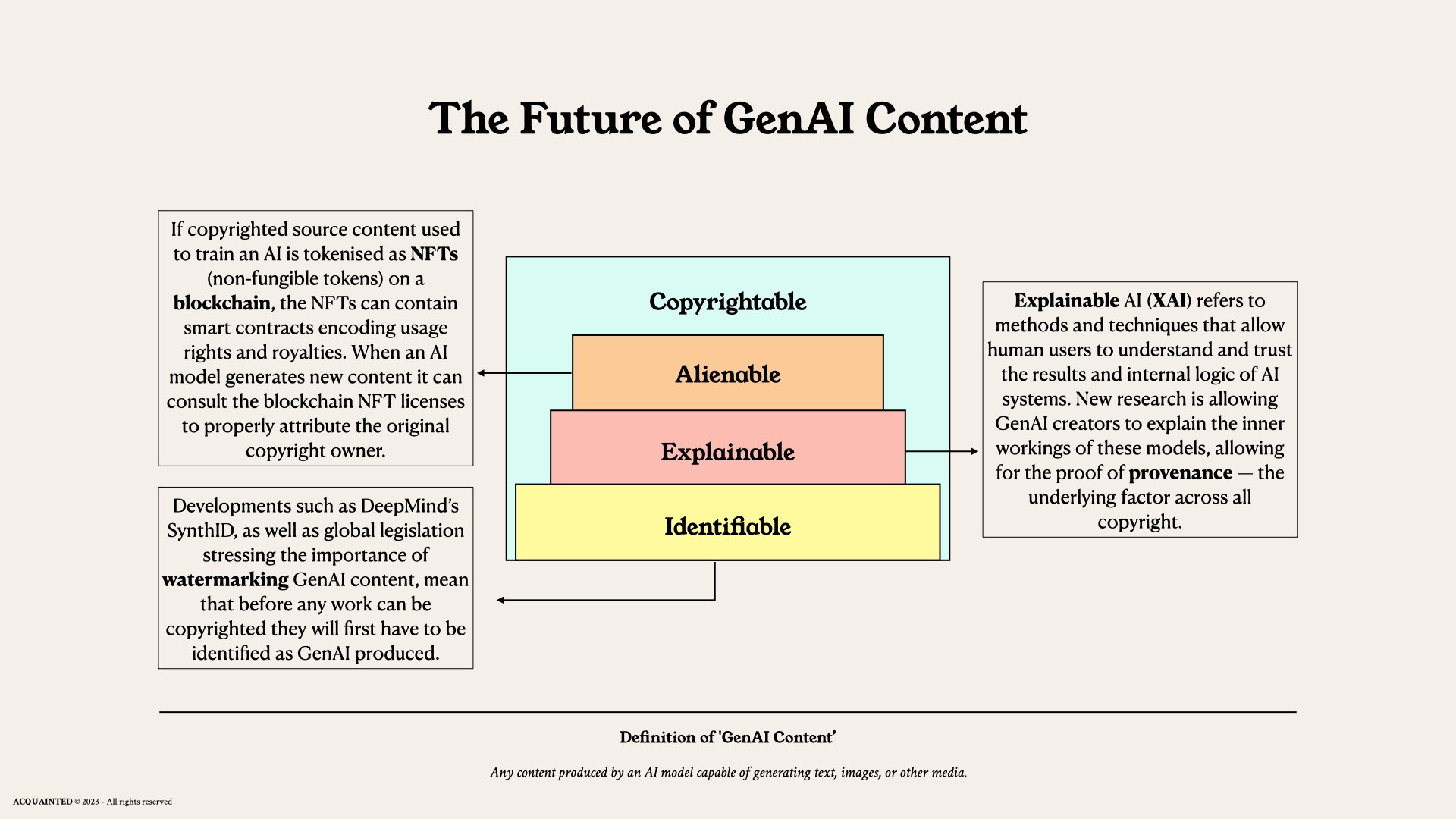

The dust is far from settled, and as we will explore in later articles — the topic of “Silent IP” will only get louder and louder. In the meantime, we thought it useful to begin envisioning a future when AI content is copyrightable, and what that might look like.

Identifiable

As was pretty clear from our talk "AI Ethics & Regulations Across Borders" (download the free booklet here), the world is a complex place. In such a polarised environment, it came as a surprise to no one that this meant the same for how different regions are approaching AI regulation.

However, that said, similarities are arising. From China to California, the E.U. to the U.K. it seems that watermarking—a technique where you hide a signal in a piece of text or an image to identify it as AI-generated—has become one of the most popular ideas proposed to regulate GenAI outputs.

Last month, Google's DeepMind rose to the challenge, releasing SynthID, a tool which is designed to watermark and identify AI-generated images. This technology embeds a digital watermark directly into the pixels of an image, making it imperceptible to the human eye, but detectable for identification.

It's clearly needed. Outside of issues around ownership, deepfakes are hitting a level of maturation that could easily fool even the most eagle-eyed tech head. With election years in both the U.K. and the U.S.A. on the horizon, pressures were building for something to be done.

Already questions arise when it comes to watermarking. Is detection universal? If so, how can we prevent people from claiming work is synthetic when it is not? On the other hand, not allowing everyone to detect such media cedes considerable power to those who have it. Who gets to decide what is real?

The quagmires around GenAI run deeper and deeper, but what is clear is that before any GenAI work can be copyrighted first and foremost it will have to be watermarked as such in order to qualify.

Explainable

One of the keys to copyrightable AI will be developing AI systems capable of explaining their creative choices. Current machine learning methods allow computers to produce novels, artworks and music by analysing and mimicking patterns in training data. But the inner workings are complex and opaque. To convincingly make a copyright claim on an output that was made in tandem (or solely) by these models we will need engineering breakthroughs that make systems more interpretable and in doing so, allow authors to prove provenance — the baseline for all copyright.

This will come in the form of Explainable AI (XAI), which allows machines to articulate the intent and reasoning behind their creative output. If an AI can provide a detailed account of how itself or its user added original expression to build upon existing works, selected certain visual elements, or chose specific words — it begins to show evidence of creativity akin to how copyright works today.

The technology is not yet advanced enough, but the winds are shifting. Last month a paper “XAI in the Arts” involved authors making a music generation model more explainable by exposing parts of the model architecture (latent space dimensions), mapping those dimensions to musical attributes, and providing an interactive UI to show how tweaking dimensions affect output. This increased explainability could shed light on the lineage of AI-generated content by revealing relationships between inputs, model components, and outputs — giving credence to arguments around argument and originality.

Sceptics who insist creativity requires human consciousness forget that copyright law has never formally defined creativity this way. Judges instead consider originality and independent effort, and current copyright law also doesn't require creators to fully understand their own creative process. After all, many authors would struggle to explain exactly how their choices lend to original expression — but they can prove the labour of their fruits.

As AI gains more capacity to independently generate and explain its workings, it moves closer to meeting originality criteria. Similar debates occurred with photography and film when new technologies sparked fears creativity would be automated away. Both became copyrightable and coexist with human creators. More recently, we see software that is copyrightable based on the code itself rather than the codes function. AI will be the same and just as at school — you’ll get your marks when you show your working.

Alienable

Blockchain technology could provide a framework to track this relationship. If copyrighted source content used to train an AI is tokenised as NFTs (non-fungible tokens) on a blockchain, the NFTs can contain smart contracts encoding usage rights and royalties.

When the AI generates new content, like text, images, or music, it can consult the blockchain NFT licenses to properly attribute the original copyright owner. If the license says "no derivatives", the AI would know not to generate derivative content.

However, some licenses will allow for derivatives and newly generated content could itself be minted as an NFT with embedded information crediting the AI model's training data sources. These smart contracts could encode royalty distribution, so if the AI content gets licensed or sold, automatic payments can be made to the original training data copyright holders based on their contribution to the creation.

The blockchain would have to work in tandem with XAI in order to exclude works that the newly generated output is not derivative of. After all, if your GenAI output only used X of the data, and had no input from Y or Z — then clearly there is no reason for royalties to be paid for not using it.

Of course, the models themselves took a village to create, but the goal should always be about properly balancing the rights of original data contributors with incentives for AI innovation. We must not sacrifice progress on the altar of protectionism, but clearly, we must find solutions which do not discourage others to innovate or embark on creative endeavours.

Potential outcomes

While the above serves as a baseline framework for a potential future. There are many moving parts and many potential outcomes. For example, fair use could be expanded further to give developers carte blanche, or we could even see models recognised as legal “people” akin to how we recognise corporations who can own intellectual property themselves. Currently, we just don’t know and there are no obvious answers.

But it stands to reason that by identifying what is and what is not synthetic, by building on past precedences such as provenance with XAI, and by establishing ownership at a more detailed level than ever before through the blockchain, we may well see a future wherein Generative AI works will be copyrightable. While the future is uncertain, one thing is abundantly clear: our current predicament is like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole, and simply isn’t working.

If you would like to keep up to date with how to implement GenAI safely, securely and efficiently in your organisation, follow us on Linkedin. Alternatively, get in touch to hear about our three-tiered approach to GenAI and gain your competitive edge.